Posted January 14, 2018 06:35 pm

By Tom Corwin Staff Writer

THE AUGUSTA CHRONICLE

Drug Therapy Discovered at MCG Being Used to Treat

Rare Form of Brain Cancer in Children

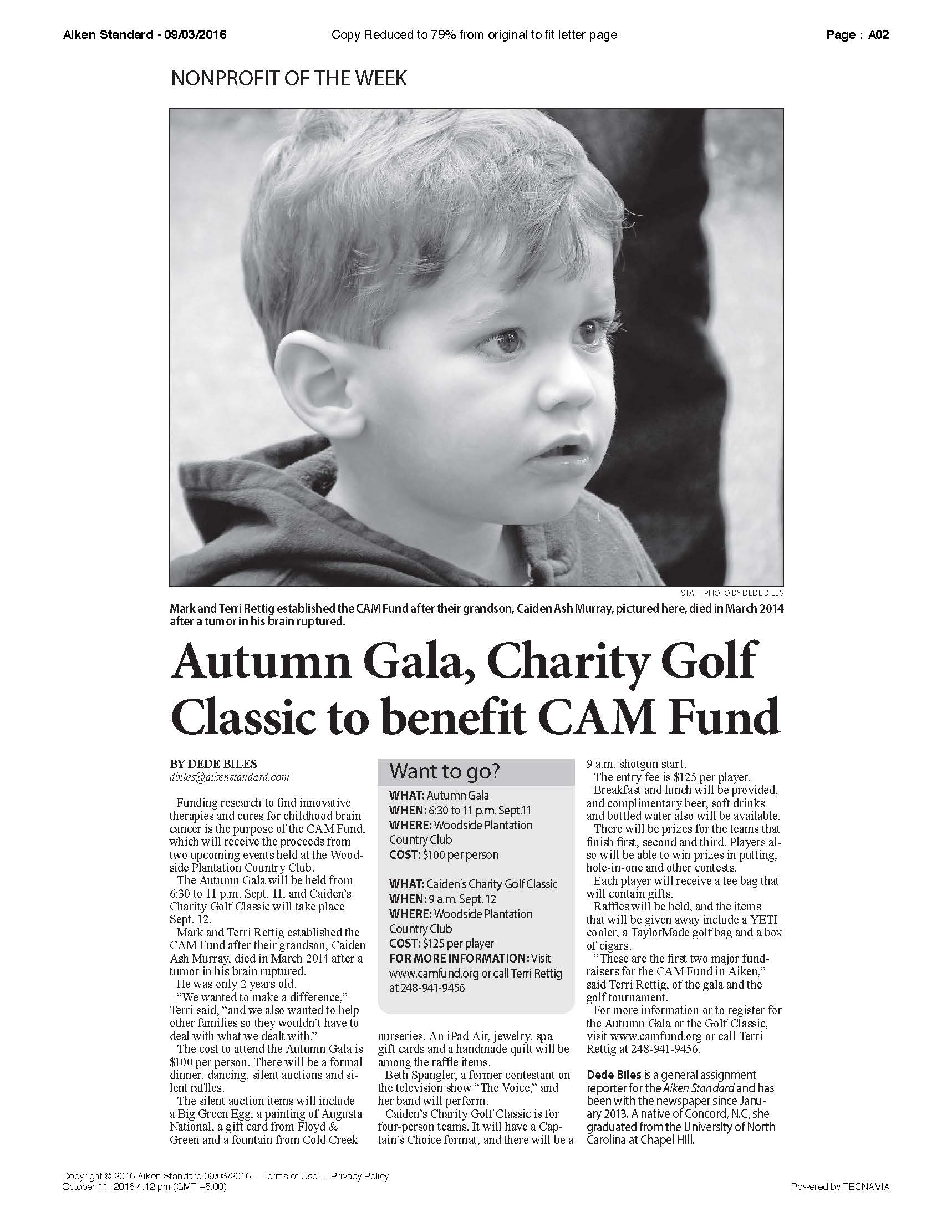

Of the kids playing and running around the room inside the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, it is impossible to pick out Kaiden Morrell, 9, as the one whose brain harbored a rare and deadly tumor.

“He never changed. He was always the same,” said his mother, Shaferriah Bradley of Allendale, S.C. “When he first started taking the radiation, he started throwing up from time to time. But his attitude, his behavior never changed.”

Part of that may be due to a unique clinical trial at the hospital and Georgia Cancer Center at Augusta University where Kaiden was one of the first kids with his kind of cancer to receive a homegrown therapy first discovered at Medical College of Georgia. The therapy is a drug called Indoximod that blocks an enzyme called indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase or IDO for short.

Its role was first discovered at MCG in 1998 and the principal investigator on the trial, Dr. Ted Johnson, was part of the team at MCG that first wrote about the way tumors manipulate the enzyme to evade the body’s immune system. The drug is already being used to treat 42 children who have brain tumors that resisted other treatments or reoccurred but only recently has the clinical trial opened up a new arm to treat children with Kaiden’s cancer.

The tumor is called a diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or DIPG and it is among the worst childhood cancers. There are only between 200-400 diagnosed a year in the U.S. and the median survival after diagnosis is nine months, according to the Michael Mosier Defeat DIPG Foundation. Less than 1 percent survive five years, compared to around 83 percent for all childhood cancers, according to the foundation.

Surgery is not an option because the tumor forms in an area deep in the brain called the pons, and it is spread throughout. That area also controls many vital functions, like sight and breathing, and it was one reason that Johnson said the clinical trial, which begins as a safety and dosing trial, wanted to avoid treating children with a drug that had no human safety data yet.

“A little bit of swelling there can cause a lot of side effects, and some of those are very dangerous,” he said.

But it is also a tumor that has no effective treatment – radiation shrinks the tumor in about 70 percent of the cases but only for a while and it typically adds only about three months to survival, according to the DIPG Foundation. Over 250 clinical trials in the last 30 years have failed to find a drug that can increase survival.

The need is certainly there but Johnson and those overseeing the clinical trial have been cautious about making sure the benefit of adding new cancers to the trial outweighed any potential safety risk. Of the children with relapsed or resistant brain tumors, they have been slowly but steadily increasing the dose to reach the highest dose they had planned to give, Johnson said. The drug, a form of immunotherapy, is given with radiation and other chemotherapy where appropriate and so far has not appeared to be toxic, he said.

“For most kids this is well-tolerated and by and large it is not a hard treatment to deliver or for the kids to take,” Johnson said, because it is a pill. “So we’ve had some kids who have had metastatic disease to the brain stem that were treated safely and that made us feel more comfortable about coming back around to the DIPG cases.”

But for there to be a new arm to the clinical trial, there would need to be new funding. That’s where the Press On Fund and the CAM Fund came in.

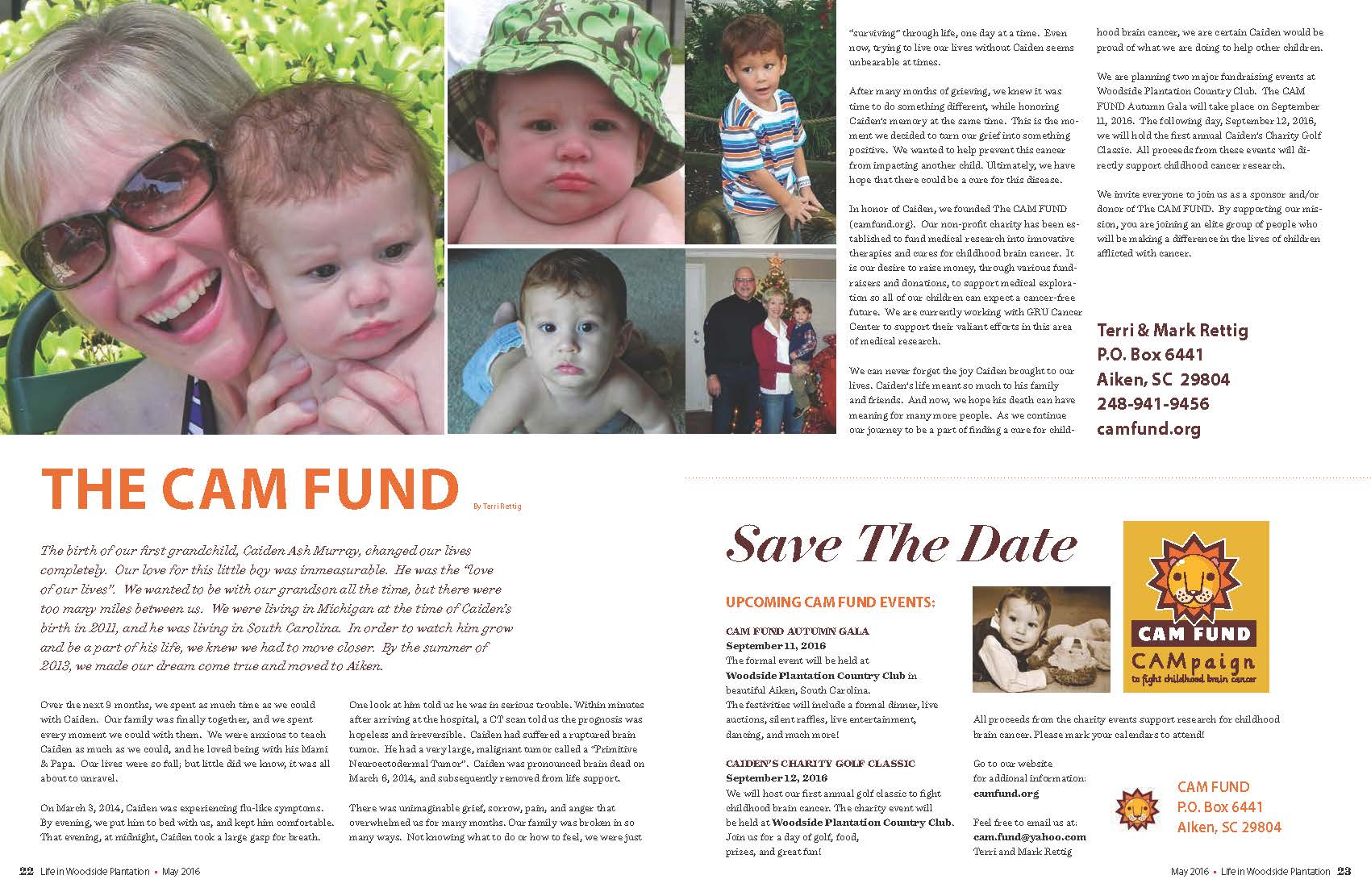

Press On was founded in part of by Turner and Tara Simkins, whose child, Brennan, battled acute myeloid leukemia with an astonishing four bone marrow transplants before finally achieving remission. CAM Fund, in honor of Caiden Ash Murray, was established by the Rettig family after their two-year-old grandson died from a massive brain tumor that went undetected until it ruptured and caused him to stop breathing and die. CAM Fund aligned with Press On last year to make a $150,000 donation to the IDO trial so that DIPG children could start getting the treatment.

“We just want to help children,” Mark Rettig said. “If we could honestly save one child it would be worth all we have.”

“We’re hopeful they are laying the foundation right here in Augusta for what could potentially be a major game-changer,” Turner Simkins said. Drug companies generally aren’t interested in funding research into children’s cancer so “grassroots organizations like ours have to pick up the slack,” he said.

But even with the new funding, there wasn’t enough to support the research costs until Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation upped its commitment to the trial again, Johnson said. The foundation, which has supported the IDO research even before the clinical trial, added $658,000 over two years to bring its total commitment to $1.5 million, he said. The foundations are “providing the funds that are sorely needed so that these patients can have access to that care,” Johnson said.

Still, he is cautious about overstating the results of the earlier trial and in fact frames them in the most limited way.

“I can’t say that this treatment is effective at this point,” he said. “We haven’t enrolled enough patients, we haven’t treated enough patients and we’re in the very, very earliest phases of treating any DIPG patients. But if it works at all, it is likely to work across several tumor types that occur in kids. For that reason, we’ve had DIPG sort of on our radar all along. The big news is frankly that we’ve crossed the bridge from enrolling and treating kids with relapsed brain tumors to enrolling and treating kids who just got diagnosed for the first time.”

Now, children like Kaiden are getting it as a first treatment, along with radiation and chemotherapy.

“We are combining the Indoximod with those tumor-damaging treatments in order to get maximal immune effect and this might be the right setting for immunotherapy to have the biggest impact as upfront treatment,” Johnson said.

For a mother whose child has been diagnosed with a deadly brain tumor, Bradley considers it “a miracle” that it happened when and where it did. On Oct. 19, Kaiden was playing football during recess when he fell and hit his head on concrete. The school sent him to the Emergency Room and a CT scan showed something unusual, Bradley said. Kaiden was transferred to the children’s hospital for another CT and then an MRI. That is when they found the DIPG tumor, she said. The family got the bad news a couple of days later, Bradley said.

“That it was rare and it was deadly,” she said quietly, as Kaiden played in the corner with his 1-year-old sister, Skylar. “Because of the location of it, they couldn’t do surgery. They gave him four months to live at first.”

But they also told her about the clinical trial there and Kaiden was soon enrolled in it. Then on Dec. 14, he had another scan and something remarkable happened, she said: the tumor was gone.

“It showed it went away,” Bradley said. It goes against everything she had read about these tumors, which was that “no one ever gets rid of it,” she said. So for now, the family returns for labs and Kaiden continues taking the drug and “I pray,” Bradley said. “I just hope it stays that way.”

Kaiden’s news draws a “Wow,” from Rettig.

“That’s why we’re doing what we’re doing,” he said. “We hope to do more.”

Reach Tom Corwin at (706) 823-3213

or tom.corwin@augustachronicle.com